External Commercial Borrowings

External Commercial Borrowings (ECBs): A Gateway to Global Finance for Indian Entities

In today’s interconnected world, Indian businesses are not limited to domestic funding. They can tap into international sources for loans—one key route being External Commercial Borrowings (ECBs)

What Are ECBs?

ECBs are loans taken by Indian companies from foreign lenders. These loans can be in Indian Rupees or any freely convertible foreign currency.

Who is the Regulator?

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governs ECBs under the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA), 1999, specifically through its Master Directions. These guidelines define who can borrow, from whom, and under what conditions among other conditions.

Two Routes to Raise ECBs

- Automatic Route – No prior RBI approval needed; just go through your bank (Authorised Dealer Category-I).

- Approval Route – Prior RBI approval mandatory requirement

Who can borrow?

Entities eligible for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and others like:

- Port trusts

- SEZ units

- SIDBI & EXIM Bank

- Registered microfinance institutions

- Not-for-profit companies, societies, trusts, NGOs

Who Can Lend?

Recognised lenders include:

- Residents of FATF/IOSCO-compliant countries

- Multilateral finance institutions (e.g., World Bank)

- Foreign equity holders (Direct with min holding of 25% or Indirect with min holding of 51%) (for listed bonds/debentures)

- Foreign branches/subsidiaries of Indian banks (only for foreign currency ECBs)

End use of funds – know the restrictions

- Real estate activities

- Investing in capital markets or equity

- General working capital or corporate purposes (unless specific conditions are met)

- Repaying rupee loans

- On-lending for any of the above

Limits and Thresholds

- Up to USD 750 million (or equivalent) per financial year.

- In case of FCY denominated ECB raised from direct foreign equity holder, ECB liability-equity ratio for ECB raised under the automatic route cannot exceed 7:1.

Minimum Maturity Periods (MAMP) -

MAMP is the minimum weighted average time for which the loan must be held by the borrower.

Here’s a quick snapshot of minimum average maturity period based on loan classification:

| Purpose | Maturity |

|---|---|

| General ECBs | 3 years |

| Manufacturing companies (up to USD 50M) | 1 year |

| From foreign equity holders (for working capital/general) | 5 years |

| General ECBs | 3 years |

| Manufacturing companies (up to USD 50M) | 1 year |

| From foreign equity holders (for working capital/general) | 5 years |

| From others (for working capital/general purposes or on-lending by NBFCs) | 10 years |

| For repayment of rupee loans (capital expenditure) | 7 years |

| For repayment of rupee loans (non-capital expenditure) | 10 years |

Reporting & Compliance

- Loan Registration Number (LRN): Mandatory before any ECB transaction.

- Form ECB: Submit to your bank with loan details.

- Form ECB 2: Monthly reporting within 7 working days.

- Late Submission Fee: ₹7,500 to regularize delays.

The Currency Risk Trap

Let’s understand this through an example! ABC Ltd., an Indian company borrowed $1million from ABC Inc., a company based in the US.

- At inception of the loan

Exchange rate stood at 1$= INR 80

Total Liability = INR 80million - Fast forward 3 years - it’s time for repayment.

The Rupee has weakened and $1 = INR 90

Total liability = INR 90million. - Result?

An increase in liability by INR 10million solely due to currency fluctuations.

Additionally, since interest is paid in USD too, interest cost rises as the Rupee weakens. - How can companies manage this better?

Companies can mitigate currency risk by using hedging instruments such as forward contracts, options, or swaps to lock in exchange rates and reduce uncertainty.

What’s Changing?

On October 3, 2025, RBI proposed updates to simplify and expand the ECB framework. These are currently in draft stage, pending public comments and finalisation.

- The borrowing limits are proposed to be linked to a borrower’s financial strength and ECB are proposed to be raised at market determined interest rates.

- The end-use restrictions and Minimum Average Maturity requirements are proposed to be simplified.

- The borrower and lender base eligible for ECB transactions is proposed to be expanded to enhance opportunities of credit flow.

- Reporting requirements are being simplified to ease compliance obligations.

Why It Matters

These changes aim to make it easier for Indian entities to access global capital, boosting growth and competitiveness. Whether you are a startup in a SEZ or a large manufacturer, ECBs could be your ticket to international funding.

- Indian entities can leverage funds available with overseas group entities or other eligible lenders

- Such borrowings fall under the category of External Commercial Borrowings or ECB

- The Reserve Bank of India has provided detailed guidelines and compliance requirements for ECBs

- The article provides a quick overview of the key aspects to consider when contemplating debt funding from overseas

Regulatory landscape of Fintech companies

Navigating the regulatory maze for Fin-techs in India

- It is common knowledge that the financial institutions are the most stringently regulated institutions. Fin-techs, delivering financial services through technology, are creatures of the recent past and their regulation is a grey area and is continuously evolving.

- The argument of Fin-techs that they are “not Financial Institutions” to be strictly regulated is no longer a viable argument. As recently, Simpl, a BNPL based fintech company was asked to stop operations by RBI as internal investigations revealed contravention of Payments and Settlements Systems Act, 2007. Thus, turning a blind eye to the regulatory landscape is not a viable option for fin-techs.

Regulatory Landscape

The Regulatory landscape can be divided in twofold:

1. Regulators

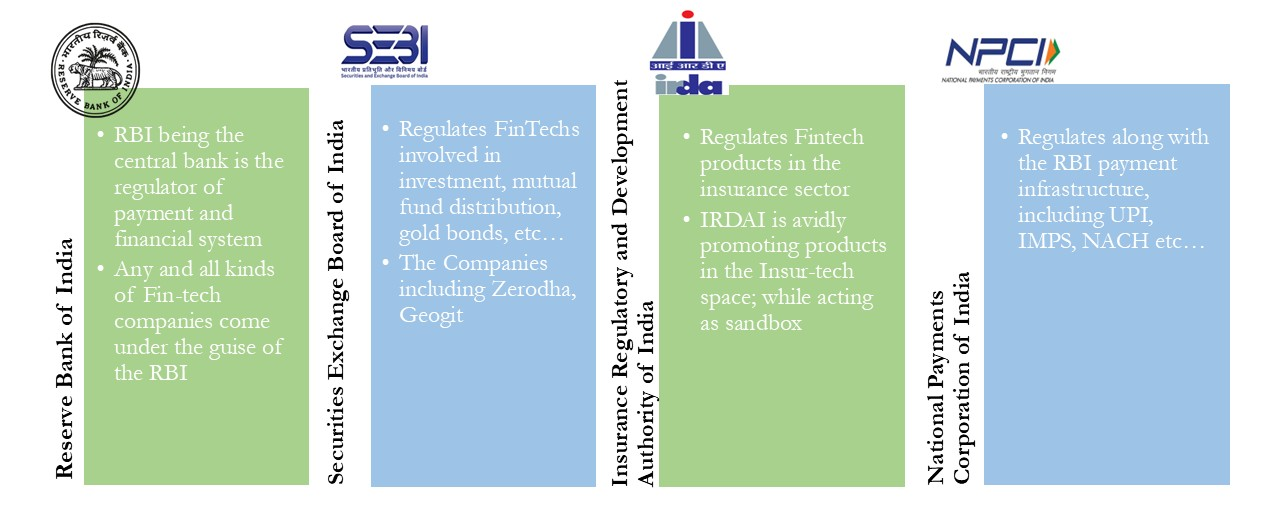

Given that the Fin-techs are a creation of the neo-tech age, there are multiple regulators and can be succinctly put as follows:

- In additional to these regulators, the fin-tech space is also regulated by Ministry of Information and Technology, Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Central Board for Direct and Indirect Taxes, State labour departments, and many more. Phew!

- This only indicates that the Indian regulators are multi-fold and multifarious, lacking a single window mechanism for fin-tech companies.

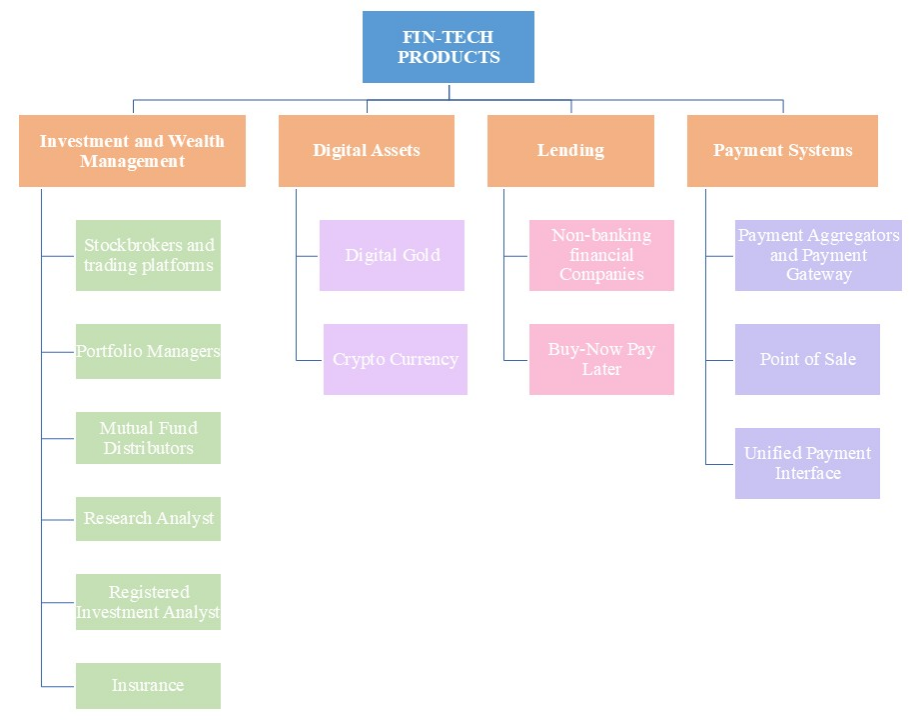

2.Product based legislations:

We can broadly classify the fin-tech products as follows and identify the applicable special laws hereinbelow:

- Investment and Wealth Management:

- Stockbrokers and Trading Platforms:

Regulation: Securities and Exchange Board of India (Stock Brokers) Regulations, 1992 along with rules prescribed by stock exchanges - Portfolio Managers:

Regulation: SEBI (Portfolio Managers) Regulations, 2020 - Mutual Fund Distributor

Regulation: Need to be registered with Association of Mutual Funds in India (“AMFI”) and follow the AMFI’s code of conduct. They are also required to pass the NISM V-A certification to receive an AMFI Registration Number (“ARN”) - Research Analyst

Regulation: SEBI (Research Analysts) Regulations, 2014 - Registered Investment Advisers

Regulation: SEBI (Investment Advisers) Regulations, 2013 - Insurance

Regulation: IRDAI (Insurance Web Aggregators) Regulations, 2017, IRDAI (Registration of Corporate Agents) Regulations, 2015 - Digital Assets

- Lending

- i.NBFC – Digital Lending Platforms:

Regulation: Master Direction on Non-Banking Financial Company – Scale Based Regulation Directions, 2023 - Buy-Now Pay-Later:

Regulation: Reserve Bank of India (Digital Lending) Directions, 2025. Some BNPL’s also obtain NBFC licenses. - Payment Systems:

- Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways:

Regulation: Payment and Settlement System Act, 2007 along with Guidelines on Regulation of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways issued by the RBI dated March 17, 2020 - Point of Sale

Regulation: Draft RBI (Regulation of Payment Aggregators) Directions, 2025 - Unified Payments Interface

Regulation: RBI Regulates UPI under Payment and Settlement System Act, 2007 and NPCI manages operational aspects of UPI

These platforms act as middlemen between investors and the capital markets, providing tools for trading, research, and financial advice through both consumer apps and business partnership models.

Digital Assets like digital gold, crypto currency are still a regulatory grey area in India. The government has only introduced taxation on such assets.

Lending has become one of the most active areas in India’s fintech landscape, driven by platforms that provide quick, convenient, and technology-enabled credit through online and mobile channels. Using advanced data tools, these companies handle everything from credit evaluation and customer onboarding to loan disbursal and repayment.

In recent years, the RBI has tightened its supervision of this sector to address issues related to consumer safety, operational transparency, and potential gaps in regulatory compliance.

Payment systems facilitate the transfer of funds between individuals, and entities. This acts as a backbone in this digital economy.

Conclusion:

The regulatory environment governing the fintech industry in India is vast, multifaceted, and continuously evolving. With multiple regulators, complex product-based legislations, and increasing oversight from authorities like the RBI and SEBI, compliance is no longer optional. Fintech companies must approach regulatory obligations with serious consideration and seek expert professional guidance to navigate these intricate frameworks. Proactive compliance and sound legal consultation are essential to avoid regulatory hurdles and ensure sustainable, lawful business operations in an increasingly stringent ecosystem.

- Fin-tech industry is rapidly growing due to digitalization and government initiatives for promoting financial inclusion across India.

- Given the strict and penal nature of regulations for finance Industry, it is important that businesses in fin-tech industry be appraised of the regulations applicable to them to avoid any future repercussions.

- In this article, we give a bird’s eye view of the regulatory landscape for fin-tech companies in India.

Article on Reverse Flipping structures

Reverse Flipping – Return to Homeland

A. What is Reverse Flipping

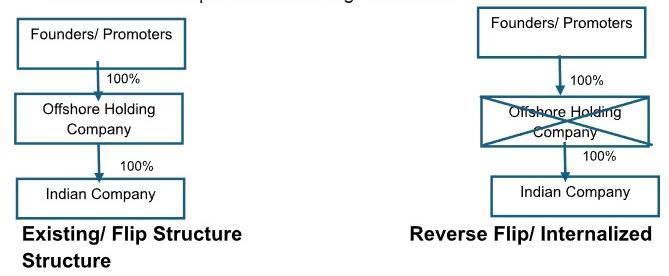

- Reverse flipping is when an Indian-founded company, after incorporating its parent company overseas for advantages like access to global capital and favorable tax regimes, shifts its legal domicile and operations back to India.

- This counter-trend to the earlier "flip" is driven by India's improving economic landscape, more favorable government policies etc., allowing these companies to become wholly Indian entities once again.

- This has been captured in the diagram below:

B. Why companies preferred overseas jurisdiction

Companies earlier preferred to set up in overseas jurisdictions on account of the following reasons (included but not limited to)

- Ability to list on overseas stock exchange, attract a larger investor base, access to foreign capital via offshore Venture Capital

- Achieve Higher valuation in foreign markets providing attractive exit

- Increased Intellectual Property protection (Stringent IP protection laws)

- Favorable regulatory requirements, avail tax benefits resulting in ease of doing business

- Lucrative global markets and brand recognition

- Favorable tax regimes for repatriation of profits to investors/ exit

The jurisdictions favoured for flipping were Singapore, UAE, Netherlands, Luxembourg, the Cayman Islands, Mauritius, the United States, and the United Kingdom

C. What is the drive to shift back to India

In the recent times, many Indian Companies have considered to return back to India majorly on account of the following:

- Investor and business friendly reforms made in Indian tax and regulatory regulations viz. Ease of the regulatory compliances – deployment of digital platforms for regulatory filings and compliances, reduction in tax rates etc.

- Demographic advantage – Massive customer base, youthful and dynamic workforce, competitive costs of workforce etc.

- Increased access to the capital markets – Maturity of Indian IPOs market viz. measures taken by SEBI to curtail the approval timelines, streamlining the processes etc.

- Magnificent growth opportunities in diverse sectors in India boosting the return of investment

- Massive digital growth, digital infrastructure (such as UPI), acting as a global technology hub, recent thrust to AI, blockchain development etc.

- Emergence of GIFT City - with tax incentives, relaxed FEMA regulations, and access to international listing opportunities

- Strategic Global positioning viz. preferred alternative destination for manufacturing, strengthening global ties viz. FTAs with major economies like EU, UK etc.

D. Ways of Reverse Flipping

Some of the prevalent structures considered for reverse flipping to Indian jurisdiction are as follows:

1. Inbound Merger of offshore Hold Co into the India Co

Offshore Hold Co would be merged with the Indian Co. In consideration of merger, India Co would issue shares to the shareholders of the offshore Hold Co i.e. founders/ promoters

Key Tax and regulatory considerations

- Income-tax

- Merger to be tax-neutral subject to prescribed conditions

- If India Co has carried forward losses, such losses would lapse

- GAAR implications if transaction lack commercial substance

- Valuation requirements to be complied with

- Tax implications as per the laws of the overseas jurisdiction to be considered

- Company Law

- Inbound mergers to comply with section 234 of the Companies Act, 2013 (“CA, 2013”) – Fast Track Merger provisions under section 233 of the CA, 2013 apply

- Company law of the Hold Co jurisdiction to permit the inbound merger

- FEMA

- FEMA (Cross Border Merger) Regulations to be complied with - issue of shares to comply with pricing guidelines, entry routes, sectoral caps etc. under FEMA FDI regulations

- Valuation of India Co and Hold Co to be done as per internationally accepted valuation principles

- RBI approval required – compliance with the FEMA (Cross Border Merger) Regulations deemed as prior RBI approval

- Stamp Duty implications in the respective state to be considered

2. Transfer of shares of India Co by Hold Co to Founders/ Promoters

- Under this option, Hold Co transfers the shares of India Co to Founders/ Promoters (consideration to remain outstanding)

- Hold Co to liquidate and distribute its net assets to Founders/ Promoters (shareholders)

Key Tax and regulatory considerations

- Income-tax

- Transfer of shares – Subject to capital gains tax in India, Exemption under the respective DTAA may be explored.

- Valuation provisions under IT Act to be complied

- Withholding taxes to be deducted - Section 195 of IT Act

- Liquidation of Hold Co - No India tax implications for Hold Co. For non-resident promoters, No India tax implications. For resident promoters (LLP), implications as per section 46. Laws of overseas jurisdiction to be considered.

- Carried forward business losses in India Co would lapse

- Company Law

- Changes to the shareholding of India Co to be captured

- In case of liquidation, the laws in country of Hold Co to be complied with

- FEMA

- Transfer of shares – For Transfer between non-residents, Valuation norms/ reporting as per FEMA FDI regulations not required. For transfer to resident promoter (LLP), Valuation and reporting requirements to be complied with

- Stamp Duty implications on transfer of shares to be considered

3. Swap of shares of Hold Co against the shares of New India Co

- Shareholders of Hold Co. to set up a New India Co – Shareholders to transfer the shares of Hold Co to New India Co. in exchange of shares of New India Co

- Hold Co to liquidate and distribute its assets and liabilities (including shares in the existing India Co) to New India Co.

Key Tax and regulatory considerations

- Income-tax

- Indirect transfer tax implications may arise for non-resident promoters. For Indian promoters (LLP), swap would be taxable

- Valuation requirements under IT Act to be complied

- Withholding taxes to be deducted as applicable

- Liquidation of Hold Co - No India tax implications for Hold Co. Taxability on New India Co as per section 46

- Liquidation of Hold Co - No India tax implications for Hold Co. Taxability on New India Co as per section 46

- Carried forward business losses, if any, in India Co may lapse

- Company Law

- Investment thresholds under section 186 of CA, 2013 to be complied with by New India Co

- Changes in shareholding of New India Co and existing India Co to be recorded – Recording of Investments in New India Co.

- In case of liquidation, the laws in country of Hold Co to be complied with

- FEMA

- Permissible as per FEMA regulations

- Valuation norms under both FDI and ODI regulations to be complied with

- However, very important that ODI limits under FEMA ODI regulations are complied with – if not complied, RBI approval required - other consequences in case of non-compliances

- Suitable reporting/ filing to be made under the FEMA FDI/ ODI regulations

- Liquidation of Hold Co - Pricing guidelines, reporting requirements under FEMA ODI regulations to be complied with

Other ways to undertake reverse flipping include Re-domiciliation of offshore Hold Co to India

E. Companies which have reverse flipped their structures recently

Few companies which have adopted reverse flipping structures to return to India are below:

- Phone Pe – Reverse Flip from Singapore - share transfer

- Groww – Reverse Flip from USA - Inbound merger

- Pepperfry - Reverse Flip from Singapore - Inbound merger

- Flipkart – Redomiciling Singapore parent entity to India

- Zepto – Reverse Flip from Singapore - Inbound merger

F. Consideration of GIFT IFSC as a hub for Reverse Flipping

IFSCA introduced International Financial Services Centres Authority (Listing) Regulations, 2024 to provide access to global capital without domestic listing and has set up Padmanabhan committee to develop a plan.

Key recommendations made by the Committee for reverse flipping to GIFT IFSC

- GIFT IFSC - considered as nodal office for incorporation and other regulatory approvals

- Tax neutral structure for relocation of Hold Co and its shareholders

- Grandfathering for existing investment of Hold Co

- No lapse of losses of the India Co

- Participation exemption for GIFT IFSC Hold Co on levy of capital gains tax

- Concessional tax regime for Dividend in the hands of GIFT IFSC Company

Once the above recommendations are finalized, GIFT IFSC would be a preferred destination for reverse flipping. Companies to keep a close eye on the finalization of these recommendations.

Power of Intangibles - An Indian Perspective

Valuation of Intangibles: An Indian Perspective

Introduction

In today’s knowledge‑driven economy, a company’s true value often lies in what cannot be seen on its balance sheet. Intangible assets—brands, trademarks, patents, customer relationships, source codes, know-how’s, and human capital—have become the new contributors of growth. Globally, many MNC firms derive a majority of their market value from intangibles and India is no exception.

Conventional Valuations to Brand Value: A Shift in Indian Valuations

Traditionally, Indian businesses were valued by their earning potential or in some case by their tangible assets—land, machinery, inventory, and buildings. This has taken a paradigm shift in a digital and services‑led economy. Today, a startup with few physical assets can command a billion‑dollar valuation solely on the strength of its technology, brand value, customer relationships, goodwill and other intellectual properties.

When Nykaa listed, for instance, its physical assets were limited. But investors back‑valued its strong brand and customer loyalty. Similarly, Indian IT majors like Infosys and TCS derive the lion’s share of their enterprise value from their IPs, proprietary platforms, and deep client relationships rather than heavy plants or equipment.

A striking example is Flipkart’s acquisition by Walmart in 2018. Walmart paid US $16 billion for a 77% stake—implying a total valuation exceeding US $20 billion—despite Flipkart having minimal fixed assets. Walmart wasn’t acquiring warehouses or factories; it was buying reach, brand trust, and data.

Intangibles: The Invisible Asset That Commands Premiums

Brand Value

In India, brand value often drives valuation multiples well beyond what physical assets justify. Taking Hindustan Unilever (HUL) as an example: its market capitalization is approximately ₹5.7 lakh crore as of November 2025, and it’s trading at a price-to-book ratio above 11x. Its factories and machinery can be replicated, but the consumer trust in its brands like Surf Excel and Dove is far harder to reproduce. That trust allows HUL to command premium pricing and retain investor confidence.

A contrast in the Indian FMCG landscape is Patanjali versus Dabur. While Patanjali rapidly expanded distribution, concerns over its governance, product consistency, and brand sustainability caused its valuation multiples to shrink. Meanwhile, Dabur, with over 135 years of heritage, continues to command stable multiples—testament to how long‑term brand and reputation resilience matters more than reach alone.

Intellectual Property, R&D and the Innovation Premium

In sectors like pharmaceuticals, biotech, and software, intellectual property is often the main value driver. Consider Biocon: its market capitalization is around INR 52 thousand crores as of November 2025, and its stock often reacts sharply to R&D breakthroughs and regulatory milestones. In such businesses, patents, licensing deals, and pipeline potential overshadow factories or land.

Customer Networks & Platform Economics

Intangibles play a central role in consumer tech and platform businesses. Paytm, at its IPO, was valued at nearly ₹1.4 lakh crore largely on the strength of its registered users and merchant network, not merely on its earning potential or its assets.

In non‑digital sectors too, customer loyalty and network effects matter. Amul, structured as a cooperative, does not own vast factories proportional to its reach, but it’s the bond with its registered consumers which acts as a powerful intangible.

Valuing Intangibles: Methods & Practical Hurdles

Most Common valuation approaches:

- Relief‑from‑Royalty Method (Income Approach) – Brands, Trademarks, Patents etc.

- Multi Period Excess Earnings Method (Income Approach) – Customer relationships, Tech Platforms, Non-compete etc.

- Replacement Cost / Reproduction Cost (Cost Approach) – Workforce, IPs which are generally not the primary business drivers

Yet in India, implementing these has challenges:

- Lack of comparable benchmarks and data in public domain

- Identification of primary business drivers and applying the appropriate valuation methodologies

- Revenue / Profits attribution in case of valuing multiple Ips

- Unrecognized IP’s in Books

- Dependence on Subjective Assumptions

Conclusion: Recognize What Lies Beneath

In India’s evolving valuation landscape, ignoring intangibles is as good as turning our back to reality. From Flipkart’s multibillion-dollar acquisition to HUL’s market cap built on its customer base, we see that real value often hides beyond books and numbers. As India pivots deeper into digital and service economies, intangibles—brands, patents, trademarks, customer relationships, technology platforms, human resource capital will matter even more.

For valuation professionals and investors, the challenge is to supplement conventional valuation models with a detailed assessment of value-generating intangibles. Only then can businesses be fairly valued. Companies should not be penalized in their valuations for having invisible yet powerful assets in the form of intangibles.

M&A Made Simple: How Deals Shape India’s Business Landscape

India's M&A scene is booming. From billion-dollar tech deals to strategic healthcare mergers, the country is becoming a hotbed for corporate restructuring. But what does it really take to pull off a merger or acquisition in India?

Why India is a Magnet for M&A

India's economic growth, investor-friendly reforms, and booming sectors like fintech, renewable energy, and healthcare are attracting global attention. With relaxed FDI norms and a surge in IPOs, companies are seeing India as a land of opportunity.

Take the Walmart-Flipkart deal—a landmark acquisition that showcased India's potential in e-commerce. Or the HDFC Bank-HDFC Ltd merger, which created a financial powerhouse.

Types of M&A – With Examples

There are different types of M&A Transactions. Here's a simple breakdown of the types with examples to relate -

- Horizontal Merger: Two companies in the same industry join forces.

Example: Vodafone India and Idea Cellular merged to become one of India's largest telecom operators. - Vertical Merger: Companies at different stages of the supply chain merge. Objective is to improve operational efficiency, reduce costs, reduce competition, increasing market share in a particular industry, benefit from the assets, capabilities and Intellectual properties acquired

Example: Reliance Industries acquiring Network18, integrating media into its digital ecosystem. - Congeneric Merger: Companies in related industries but different products.

Example: A beverage company acquiring a snack brand. - Conglomerate Merger: Companies from unrelated industries merge. The principal reason for a conglomerate merger is utilization of financial resources, enlargement of debt capacity, foray into diverse businesses.

Example: Tata Group's acquisition of Corus Steel, expanding into global steel manufacturing. - Market-Extension Merger: It is done with the objective to expand geographical reach and customer base.

Example: A South Indian food chain merging with a North Indian counterpart. - Product-Extension Merger: Merger takes place between companies offering related products in the same market. It is done with the objective to broaden product lines and enhance customer offerings.

Example: A smartphone brand acquiring a smart accessories company.

Takeovers vs. Acquisitions

A takeover is when one company gains control of another—often by buying a majority stake. An acquisition can be more strategic, involving asset transfers or business restructuring. This can be through a Slump sale for instance.

Example: Zomato's acquisition of Blinkit was a strategic move to enter quick

Legal & Regulatory Maze

There are multiple regulations that come into play during a Corporate Restructuring Action. Here are a few common and significant ones -

Company Law

- Scheme involving mergers, demergers etc. must require approval from NCLT.

- Compliance with the provisions of Section 230 to 232 of the Companies Act (viz. approval from shareholders, creditors, obtaining valuation, approval from other government authorities etc.)

- In cases of merger between holding and wholly owned subsidiary entities, fast track merger procedure under section 233 of the Companies Act needs to be complied with (Approval from Regional Director instead of NCLT)

- In case of cross border mergers, provisions of section 234 of the Companies Act needs to be complied

- In case of takeover by way of investment in new shares of the Company, provisions of section 186 of the Companies Act relating to investment limits needs to be complied with

- In case of preferential allotment of shares, valuation of shares from registered valuer

SEBI Rules

- If acquiring 25% or more in a listed company, an open offer is mandatory.

- Preferential allotments must meet pricing and lock-in norms.

- Stock exchanges must approve merger schemes before NCLT filing.

- Submission of valuation reports, auditor's certificate, no objection letters from lenders is also a prerequisite before NCLT filing

Competition Law

Where a combination (acquisition or merger) crosses the Assets or turnover related thresholds provided under Competition Act, 2002, notification to Competition Commission of India needs to be made

FEMA Compliance

- Foreign investments must follow pricing norms, sectoral caps, and reporting rules under Non Debt Instruments Rules, 2019

- Outbound mergers need to comply with FEMA ODI regulations.

Income Tax

- Mergers can be tax-neutral under Section 47, but conditions apply.

- Compliance with conditions under section 2(1B) and 2(19AAA) of the IT Act and Section 47 for tax neutrality

- Conditions relating to carried forward losses under section 72A, cost of acquisition of shares in amalgamated company, holding period of shares etc. to be complied with

- Valuation reports are crucial to comply with tax laws under Sections 50CA and 56(2)(x).

Other Considerations

- GAAR: GAAR and Principal Purpose test – Arrangements are tested for substance and for arm's length pricing , to have non-tax commercial reasons

- GST: Generally not applicable if the transfer is a going concern but would need specific analysis

- Stamp Duty: Varies by state and can be significant.

Final Thoughts

M&A in India is a powerful tool for growth, diversification, and innovation. But it's not just about strategy—it's about compliance, valuation, and timing. Whether you're a startup eyeing expansion or a global player entering India, understanding the legal and tax landscape is key.

Always consult legal and financial advisors before diving into a deal. The right structure can save you time, money, and regulatory headaches.

NRI investment in India: Love for homeland meets FEMA boundaries

For many Non-Resident Indians (NRIs), investing in India is more than just a financial move—it’s a way to stay connected to their roots. Whether it’s buying a home in your hometown, backing a promising startup, or simply growing your wealth in a familiar market, the emotional pull is strong. But as with all things financial, there are regulations to comply with.

Let’s explore how NRIs and Overseas Citizens of India (OCIs) can invest in India while staying fully compliant with FEMA. From property to pensions, repatriation to reporting, here’s a summary of the key aspects to consider

FEMA: Your Investment GPS

FEMA governs all cross-border financial transactions involving foreign exchange. That includes investments made by NRIs, OCIs, and Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs). Its goal? To facilitate external trade and payments while keeping India’s foreign exchange market stable and well-regulated.

Under FEMA:

- An NRI is an Indian citizen residing outside India.

- The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is the key regulator, issuing rules, notifications, and Master Directions that guide NRI investments.

Real Estate: What You Can Own

NRIs can acquire immovable property in India—but with a few caveats. You’re free to buy:

- Residential or commercial property

- Property received as a gift from a close relative (resident Indian, NRI, or OCI)

- Property inherited from a resident or a compliant non-resident

- Agricultural land

- Farmhouses

- Plantation property

However, you cannot purchase:

You can transfer property to resident Indians or other NRIs, as long as it’s not in the restricted categories. All payments must be made through banking channels or from compliant non-resident accounts.

Repatriation vs. Non-Repatriation: Know the Difference.

- Repatriation Basis: You can send your capital and profits back abroad. It’s ideal if you want liquidity outside India.

- Non-Repatriation Basis: Your investment is treated like a domestic one. You can’t freely send the money back overseas, but you can reinvest or use it within India.

Repatriation Investments: What’s Allowed

NRIs can invest on a repatriation basis in several ways:

Where You Can Invest

- Equity instruments of listed Indian companies (via designated branches)

- Units of domestic mutual funds (with more than 50% equity exposure)

- Shares in public sector enterprises under disinvestment

- Subscription to the National Pension System (NPS)

Investment Limits for investment in listed Indian companies

- Individual NRI: Max 5% of paid-up capital

- All NRIs combined: Max 10%, extendable to 24% with shareholder approval

Mode of Payment

- Inward remittance through banking channels

- Funds from NRE account (as per FEMA Deposit Regulations, 2016)

- For stock market investments, your NRE account must be designated as a Portfolio Investment Scheme (PIS) account

- Mutual fund investments can be made from NRE/FCNR(B) accounts

- NPS subscriptions can be funded from NRE/FCNR(B)/NRO accounts

Remittance of Sale Proceeds

- Equity sale proceeds (net of taxes) can be repatriated or credited to your NRE (PIS) account

- Proceeds from mutual funds and NPS can be repatriated or credited to NRE (PIS)/FCNR(B)/NRO accounts, based on your preference

Non-Repatriation Investments: What’s on the Table

If you’re not looking to send your money back abroad, non-repatriation investments offer more flexibility and fewer limits.

Where You Can Invest

- Equity instruments of Indian companies

- Units of investment vehicles

- Capital contribution to LLPs, firms, or proprietary concerns

- Convertible notes issued by startups

These investments are treated as domestic, just like those made by resident Indians.

Mode of Payment

- Inward remittance through banking channels

- Funds from NRE, FCNR(B), or NRO accounts

What You Can’t Invest In

- Nidhi companies

- Agriculture or plantation activities

- Real estate business or farmhouses

- Transfer of development rights

Remittance of Sale Proceeds

- All sale or disinvestment proceeds (net of taxes) must be credited only to your NRO account

- No repatriation of the original investment or capital gains is allowed

LEC (NRI): The Reporting Rule You Can’t Ignore

Every time you buy or sell equity instruments on Indian stock exchanges, your Authorised Dealer (AD) bank must report the transaction to the RBI using Form LEC (NRI).

What’s your responsibility? Keep your AD bank informed. If they don’t know about your transaction, they can’t report it—and that could lead to compliance issues.

Regulatory Filing Requirement for Share Transactions When an NRI acquires shares in an Indian company—either through a primary issuance (fresh allotment) or a secondary transaction (transfer from an existing shareholder)—certain filings are mandated under FEMA. Specifically:

- Form FC-GPR must be filed for primary issuances.

- Form FC-TRS must be filed for secondary transfers.

Importantly, the responsibility for filing these forms lies with the resident party to the transaction, not the NRI investor. This ensures regulatory compliance while simplifying the process for non-resident participants.

In Conclusion

Investing in India as an NRI is a beautiful blend of emotion and opportunity. It’s a way to stay connected, contribute to India’s growth, and build wealth in a market you understand. But it’s also a journey that requires awareness and adherence to FEMA’s rules.

Whether you’re buying property in your hometown, trading stocks in Mumbai, or backing a startup in Bengaluru, make sure your investments are not just heartfelt—but also fully class="mb-20compliant

Group of Companies Doctrine: Cox and Kings and its Judicial Aftermath

What is the Group of Companies Doctrine?

The Group of Companies Doctrine allows an arbitration agreement signed by one company in a corporate group to bind non-signatory affiliates, provided certain conditions are met.

This doctrine challenges traditional legal principles like:

- Separate legal personality

- Privity of contract

- Express consent to arbitration

The Supreme Court’s Findings in Cox and Kings Limited v. SAP India Private Limited (2023)

-

The Court interpreted sections 2(1)(h) (defines “Party” as Party to an arbitration agreement) and 7 (essentials of arbitration agreement) of the Arbitration Act, 1996 (“Act”) to include both signatories and non-signatories as Party.

Further the Court highlights that the central tenet of section 7 of the Act lies in the mutual interests of the parties rather than their express consent to be bound by an arbitration agreement.

- Mutual Intent of Parties

- Relationship of non-signatory to a signatory

- Composite nature of transaction

- Performance of contract

- Participation of non-signatory

Judgments Post Cox and Kings

- Nearly two years after the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Cox and Kings Ltd. v. SAP India Pvt. Ltd., the Group of Companies Doctrine continues to evolve under the Indian arbitration law.

- A recent and notable development is the Supreme Court’s decision in Adavya Projects Pvt. Ltd. v. Vishal Structurals Pvt. Ltd. (2025), relaxed procedural requirements to join non-signatories to arbitration proceedings.

- In this case, the appellant invoked arbitration against one respondent (a partner in an LLP) but later sought to include the LLP itself and its CEO/directors in the proceedings.

- What was the problem here? It was the fact that these non-signatories had not received notice under Section 21 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, nor were they part of the original application for appointment of the arbitrator.

- The Delhi High Court upheld the arbitrator’s decision to exclude the LLP and its CEO/directors, citing procedural lapses—primarily the lack of notice and formal joinder.

Supreme Court’s Intervention

- In a significant reversal, the Supreme Court held that:

- Though service of notice under Section 21 is mandatory to commence arbitration, but non-service alone does not bar the arbitral tribunal’s jurisdiction over such non-signatories.

- The Court reaffirmed the principle of kompetenz-kompetenz—the tribunal’s authority to rule on its own jurisdiction codified under Section 16 of the Act.

- The Court clarified that while the referral court’s prima facie examination is not binding on the tribunal; the tribunal must examine the existence of factors for application of the Doctrine. The factors being language of the agreement, conduct of parties, nature of transaction etc.

- It held that the tribunal must assess whether non-signatories effectively consented to the arbitration agreement based on conduct and the terms of the LLP Agreement.

- In essence, this clarifies that absence of a Section 21 notice does not automatically exclude parties from an arbitration. Instead, the tribunal must apply the factors under Group of Companies doctrine to determine its jurisdiction over such parties.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court in Cox and Kings Limited v. SAP India Private Limited significantly expanded the Group of Companies Doctrine, allowing arbitration agreements to bind both signatories and non-signatories where commercial realities and mutual intent justify it. Post Cox and Kings, the doctrine’s scope remains evolving.

While drafting multi-party arbitration agreements, extreme caution must be exhibited in drafting joinder of party clause. However, given that this is an evolving Doctrine express exclusion of joinder of parties in arbitration agreement is surely a rickety bridge. While the Court has provided guiding factors, time will tell how consistently and concretely these will be applied to define the contours and limits of the Group of Companies Doctrine in India.

Beyond the Buzz: What Makes a Startup Truly Valuable Today?

Valuation has evolved from backroom metric to a boardroom obsession. A decade ago, it was rarely part of mainstream startup conversations—today, it’s front and center. But let’s be clear that valuation isn’t just a number on a spreadsheet. It’s a dynamic blend of founder’s ambition, strategic vision, market conditions, investor sentiment, growth trajectory, and peer benchmarks. It’s as much art as it is math.

Why valuation fell after 2023

Back in 2020-21, market optimism and the availability of low-cost capital inflated valuations across the board. Growth was the key metric. Investors overlooked losses and placed their bets on rapid market capture and the promise of future profitability. However, that approach has since shifted dramatically. Today, growth alone is no longer enough. The market demands profitability or at least a credible, measurable path to it.

In 2021–2022, Indian tech IPOs like Paytm, Zomato, and Nykaa entered public markets at highly inflated valuations, often without strong fundamentals to back them. Many of these IPOs were priced aggressively, often without solid fundamentals. Investors were betting on what these companies could become, not what they were

In response to the volatility and investor concerns, SEBI (Securities and Exchange Board of India) introduced stricter disclosure norms. Companies now had to be more transparent about their financials, risks, and future plans.

This regulatory push helped shift the focus from flashy narratives to fundamentals. IPOs in 2024–25 are showing a marked change—valuations are more reasonable, and companies are presenting clearer paths to profitability. Revenue Multiples vs. Profitability

It’s often observed that technology companies are valued on revenue multiples rather than profits. On the surface, this seems to ignore the ultimate goal of any business—profitability. But in reality, the logic is different. Profits, while critical in the long run, can be suppressed in the early years due to heavy spending on R&D, marketing, customer acquisition, and infrastructure. Revenue, on the other hand, reflects product–market fit and signals growth potential, which makes it a cleaner, comparable metric when companies are loss-making.

However, the crucial caveat is that not all revenue growth is created equal. The contrasting cases of Paytm and Zomato during their IPOs in 2021 highlight how investor sentiment diverges when revenue growth is not matched by economic fundamentals.

Case Study: Paytm vs. Zomato

| Metric | Paytm (INR) | Zomato (INR) |

|---|---|---|

| Revenue (FY 2020-21) | 2,801 Cr approx. | 1,994 Cr approx. |

| IPO Valuation | 1,49,428 Cr | 64,365 Cr |

| Revenue Multiple | 53x | 32x |

| Loss | 1,700 Cr | 816 Cr |

| Listing Performance | Loss of around 9% | Gain of around 65% |

Zomato attracted investors with strong revenue growth, higher gross margins, and improvements in contribution margins. Its business model—with commissions from restaurants, delivery charges, and advertising—offered clearer monetization opportunities. Investors believed that operating leverage would eventually lead to profitability.

Paytm, on the other hand, struggled with slowing growth, wafer-thin margins due to low take-rates on payments, and no clear profitability roadmap. Despite being pitched as India’s “super app,” the economics could not justify the global fintech-style valuations it was assigned. Within a year of its listing, Paytm’s stock had lost nearly 75% of its value.

The lesson here is clear: revenue multiples are not inherently problematic, but they must be supported by strong fundamentals. When used in isolation, they can backfire—Paytm became a cautionary tale, while Zomato was seen as a more balanced bet

Current Valuation Trends

Global interest rates have risen and inflation remains sticky, leading to tighter flows of venture capital. Investors today are more cautious, selective, and demanding when evaluating opportunities. The old narrative of prioritizing growth above all else is no longer sufficient. Metrics such as efficiency, cost discipline, customer acquisition cost (CAC), contribution margins, and profitability roadmaps have taken center stage. Growth must now be paired with sustainable unit economics.

What Defines a Strong Valuation Today

A strong valuation today is built on realistic growth expectations, efficient execution, and a clear roadmap to profitability. High GMV or user counts, which once dominated startup pitches, mean little if they don’t translate into healthy cash flows. Investors are rewarding resilience, scalability, and sustainability over momentum-driven growth.

Some of the key drivers of valuation now include:

- Numbers: Revenue, profitability, margins, burn rate, and cash runway.

- Scalability and sustainability of the business model.

- Strength and credibility of the leadership team.

- Innovation and defensible technology.

- Competitive advantages that are hard to replicate.

- Customer base quality and long-term retention.

The Bottom Line

The valuation climate has changed significantly. If 2021 was about momentum, 2025 is about maturity. Founders must move away from chasing inflated numbers and focus instead on building resilient, efficient, and profitable businesses.

The experiences of Zomato, Paytm, and Nykaa provide critical lessons. Public markets reward execution and performance, not just potential. Sustainable growth, operational efficiency, and a credible path to profitability will ultimately determine how startups are valued—and whether they thrive or fail in the long run.

Our insights keep evolving. Stay connected as we bring you new perspectives and updates on a regular basis.